The percentage of Americans who think it would be best for the United States to stay out of world affairs is at an all-time high since World War II1. This isolationist trend in public opinion is happening at a time when few things are more inevitable than the rising tide of economic globalization. In a number of recent studies, we have explored the factors driving mass attitudes toward two key features of globalization, international trade and offshore outsourcing2. That the U.S. public is so ambivalent about globalization at the same time that the health of the U.S. economy remains heavily dependent on it makes it all the more urgent that the public and political leaders share an understanding of what is at stake.

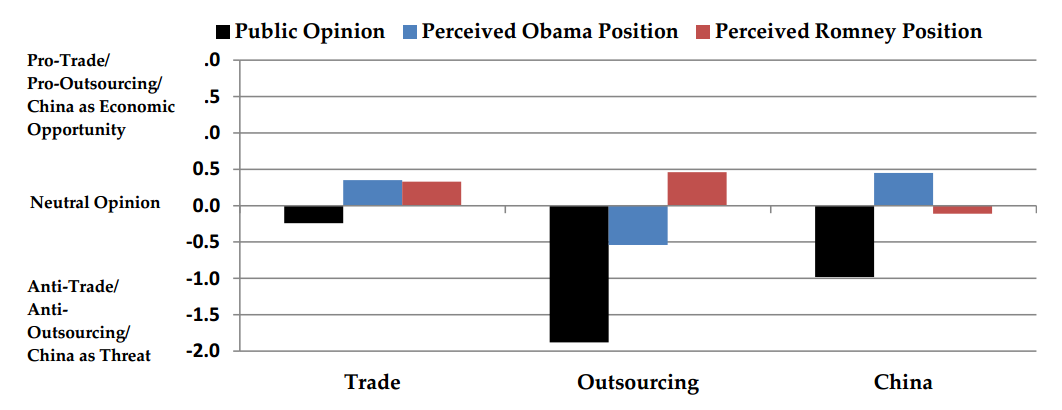

Unfortunately, there is a huge chasm between how the American public thinks about these issues compared to how social scientists and political leaders do so. The 2012 election may have only exacerbated this problem. As shown below, based on a nationally representative survey that we conducted immediately prior to the election, mass opinion is largely hostile to globalization, and the public consistently perceives its political leaders to be significantly more supportive of global economic involvement than they are themselves. Both Barack Obama and Mitt Romney were viewed by voters as more supportive of trade and outsourcing than the American public at large. Both candidates also considered China to be more of an economic opportunity, whereas the public viewed China as more of an economic threat. Below we identify some major misconceptions about the sources of these attitudes, misconceptions that may serve as impediments to smoothing a path toward economic globalization.

ECONOMIC GLOBALIZATION = JOB LOSS?

There are many possible sources of opposition to globalization, but the central focus in the U.S. has been job loss. Much of the concern over job loss has been directed at what has variously been referred to as “offshore outsourcing;” that is, the movement of part of the production process both outside the firm and overseas. Many observers worry that offshore outsourcing will lead to substantial churning in the U.S. labor market, as firms try to achieve savings by moving jobs to foreign countries where (especially less skilled) labor is cheaper. Some estimates suggest that as much as a quarter of the U.S. workforce is potentially offshorable3.

Americans have heard a great deal about outsourcing over the past fifteen years, both in media reports and in each of the past four presidential elections. Moreover, it is clear that people are not happy about this phenomenon. Based on a number of surveys that we have conducted, only 2 percent of American workers view offshore outsourcing favorably, whereas over 78 percent of workers are hostile to this phenomenon and another 20 percent have mixed views. Americans have a more favorable view of international trade than offshore outsourcing, but they are nonetheless ambivalent, with more workers opposed to trade liberalization than favoring it, about a quarter having mixed views.

It is widely believed that Americans who are concerned about free trade and outsourcing feel this way because they are losing jobs or at risk of losing jobs in the future due to these policies. And yet study after study has found no evidence to support the idea that this opposition comes from those who are most threatened economically4. Even the staunchest advocates of free trade acknowledge that it has distributional consequences that are disruptive to some people’s lives. But surprisingly, those in the occupations or industries susceptible to these disruptions are not the ones most likely to oppose to such policies.

If not because of an impact on individuals’ pocketbooks, then why are these policies unpopular? Our research suggests that attitudes toward globalization are shaped by predispositions that fall outside the economic realm. The first reason is nationalism, that is, the sense that America is superior to other countries in the world. Americans who believe that the U.S. is inherently superior are far more likely to oppose open trade and offshore outsourcing, perhaps because they consider American products and workers to be better than foreign products and workers. Second, those who express a general desire to avoid engagement with the rest of the world—whether for humanitarian or other reasons—also oppose globalization. Finally, and perhaps most remarkably, negative feelings toward people who are racially and ethnically different drives antiglobalization sentiment. Individuals who think less of so-called “out groups” within their own country (whites toward African-Americans and Hispanics, African-Americans toward whites and Hispanics, and so forth) are especially hostile to foreign commerce and offshore outsourcing. Interestingly, the extent of a person’s sense of nationalism, isolationism, and ethnocentrism tells us more about his or her opinions of globalization than what kind of job they hold, where they work, or whether they are currently unemployed.

THE IMPORTANCE OF INFORMATION

Overall, then, attitudes toward economic globalization have surprisingly little to do with economics. But there is an important sense in which they are nonetheless tied to economic perceptions. Although an individual’s own economic circumstances and background are largely disconnected from their feelings about international trade and offshore outsourcing, their perceptions of how others are affected by economic globalization are closely tied to their opinions about these outcomes. Relatively few people think that they and their families have been directly affected by economic globalization, yet many people are convinced that everyone else has been dramatically and negatively impacted.

What, then, is the source of these perceptions? To a large extent, perceptions of the impact of trade and outsourcing are shaped by media coverage and campaign rhetoric. In the United States, media coverage of trade is almost exclusively about job loss. In our content analyses of both newspapers and television, negative coverage of economic globalization completely overwhelms any coverage of its benefits. With few exceptions, there is a striking tendency for the media to focus on globalization’s adverse consequences. Reporters covering a story about a factory closing due to outsourcing do not feel a need to seek out a pro-outsourcing story to balance things out. We suspect that this has little to do with the partisan leanings of reporters; in fact, partisanship is weakly if at all related to people’s opinions on globalization. Stories about people losing jobs are concrete, easy to understand, and dramatic. The benefits of economic globalization, in contrast, are far more diffuse, technical, and difficult to explain. When local jobs are created due to open markets, few people will be aware of this fact. When jobs are lost due to outsourcing, it will be headline news.

This state of affairs suggests that political leadership and public education is sorely needed. The case for trade and economic globalization has rarely been articulated clearly to the American public. Instead, politicians fear being labeled advocates of globalization—and especially outsourcing—because of mass public opposition to globalization and this opposition’s potential electoral consequences. During elections, U.S. politicians frequently use this issue to tar their political opponents because it is well known that globalization is a source of fear and anxiety for the American public. Thus, Mitt Romney sought leverage by threatening to brand China a currency manipulator on his first day in office. And Barack Obama capitalized on negative sentiment toward Romney’s association with outsourcing via Bain Capital.

In the end, however, we suspect that the public perceptions of elite opinion outlined above are roughly on the money; there is much less disagreement between Republican and Democratic leadership on these issues than there is between the American public and its leadership within either party. Politicians understand that international economic exchange is a large and growing force on which the U.S. depends heavily. The public is simply not on board. Even very basic economic principles are not widely understood, and many politicians would prefer to manipulate this fear for electoral advantage rather than improving the public’s understanding of globalization.

The public’s lack of economic knowledge promotes both misunderstanding and misanthropy toward other countries. Consider just a few examples of widespread economic misunderstanding:

37 percent of the American public believes that trade increases the costs of the consumer products that they buy.

Only 34 percent of the American public is aware that economists believe free trade is good for the economy.

While almost 80 percent of the public has strong negative opinions of outsourcing, there is no consensus or understanding of what the term means. To most Americans, the term outsourcing by definition means outsiders benefitting at Americans’ expense.

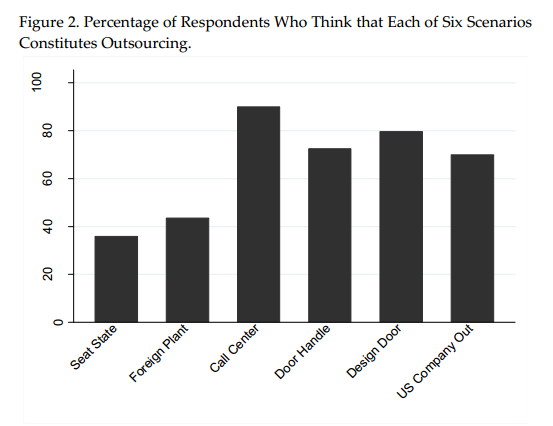

Indeed, after reading a story in our own local newspaper about “outsourcing” to the Amish, we became very curious about how the public understands this term5. As shown in Figure 2 below, there is truly little agreement on what constitutes outsourcing. In a recent survey, we asked a representative sample of American workers to indicate which of the following six scenarios constitutes outsourcing:

(1) A U.S. car company purchases seat fabric from a company in another state rather than make it themselves (Seat State).

(2) A car company in another country decides to build a manufacturing plant in the U.S. (Foreign Plant).

(3) A U.S. car company purchases the services of a company in another country to handle their customer service calls (Call Center).

(4) A U.S. car company purchases door handles for their cars from a company located in another country (Door Handle).

(5) A U.S. car company purchases the services of a company in another country to design door handles for their cars and the designs are sent via internet to the U.S. (Design Door).

(6) A U.S. car company decides to build a manufacturing plant outside the U.S. (U.S. Company Out).

Respondents were free to indicate that all of these scenarios were instances of outsourcing, that some were and others were not, or that none of them were outsourcing. Given the widespread attention that overseas call centers have received in public discussion of outsourcing, it comes as no surprise that 90 percent of our survey respondents considered this scenario to be outsourcing. About 80 percent viewed purchasing door handles from a foreign country as outsourcing, over 72 percent considered foreign designed door handles to be outsourcing, and 70 percent thought that locating a manufacturing plant outside of the U.S. was outsourcing. Over 43 percent think that a foreign company building a plant in the U.S. is outsourcing; and almost 70 percent think that a U.S. company building an overseas plant is an example of this phenomenon.

Based on three national surveys, we have concluded that the type of information to which citizens are exposed plays a crucial role in shaping preferences toward trade and outsourcing. People who understand that economists think trade is beneficial for the country overall are more likely to support policies involving globalization, even after taking into account educational and occupational differences. Furthermore, information furnished by the media helps to shape people’s attitudes toward globalization. Individuals with greater exposure to news stories and commentaries that extol the virtues of trade, for example, are significantly more likely to have pro-trade attitudes than individuals who tend to read and watch media sources that criticize trade. And this does not simply reflect a tendency for people to watch and read stories that are consistent with what they already believe: instead, media content actually alters attitudes about overseas commerce.

Taken together, our results strongly suggest that people’s attitudes about globalization are shaped far less by its economic consequences than by their views about foreign countries and people who are different. In this sense, banging the anti-globalization drum threatens to whip up nationalist and isolationist sentiment that could impede international cooperation and complicate U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. depends heavily on integration in the international economy to promote prosperity. We need a sustained and thoughtful public discourse about this issue or we risk a public backlash against it that could have highly adverse consequences for America’s international economic relations.

Endnotes

1 See, for example, Foreign Policy in the New Millennium: Results of the 2012 Chicago Council Survey of American Public Opinion and U.S. Foreign Policy.

2 For details on trade attitudes, see Mansfield, E., and D.C. Mutz, “Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest, Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety,” International Organization 63, Summer 2009, pp. 425–57. For details on attitudes toward outsourcing, see Mansfield, E. and D.C. Mutz, “US vs. Them: Mass Attitudes toward Offshore Outsourcing,” World Politics, forthcoming.

3 See Blinder, A. S., “Offshoring: Big Deal, or Business as Usual?” In Benjamin M. Friedman, ed., Offshoring of American Jobs: What Response from U.S. Economic Policy? Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009, pp. 19-59; and Blinder, A, S., “How Many U.S. Jobs Might Be Offshorable?” World Economics 10, no. 2 (April-June 2009): 41-78.

4 See, for example, the studies in footnote 2, above, as well as Hainmueller, J., and M. J. Hiscox, “Learning to Love Globalization: Education and Individual Attitudes toward International Trade.” International Organization 60, no. 2 (April 2006): 469-98.

5 Philadelphia Inquirer 29 November 2010, D1 and D7.

|

The Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. holds copyright to this material and has granted the Global Relations Forum permission to translate and republish this version on the GRF web site. The Brookings Institution is not affiliated with GRF and takes no responsibility nor makes any endorsement for the content on the GRF’s web site. Similarly, GRF takes no responsibility nor makes any endorsement for the content on the Brookings Institution’s website. |